You hear that first climbing note of “Franklin's Tower,” and it hits you all at once — Summers floating sleepily along a quiet stream. The stunning splatter of Mojave mountains and buttes as the fall eases in. Nights spent stargazing, blasted out of your gourd on DMT, listening to the wails of police sirens and gunshots echo along the streets of Indianapolis — the moments tied together by a masterpiece of an album that has seen you through it all.

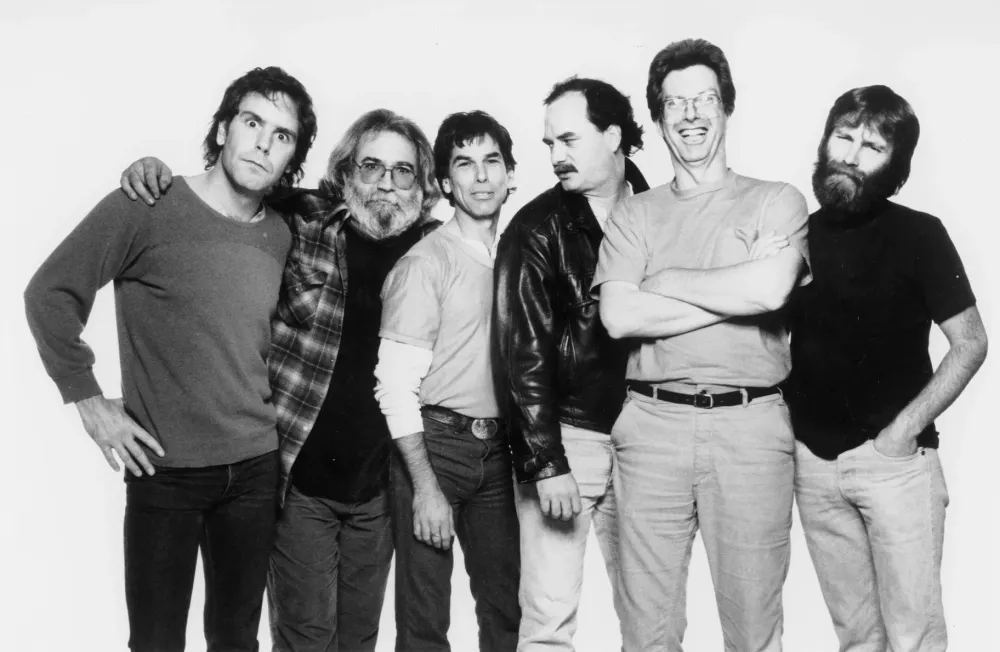

In its five decades, Blues for Allah has had plenty of time to earn its place in the hearts of deadheads and casual listeners alike. The album never broke into the mainstream space like Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty did, but it’s still a core part of the Dead’s discography with tracks that appear on Dead & Company set lists today. So, as we sit now, just two weeks from the record's fiftieth birthday, I want to take a look back on it to see what it is that's allowed this album to stand the test of time.

Blues for Allah marked the beginning of another transitionary period for the Grateful Dead. Many people think of the Dead as a psychedelic band, but they only had three hard psychedelic albums. After Aoxomoxoa, they eased off the psychedelia, playing music more akin to that of their roots: blues, country, and folk, to name a few heavy influences. That era would last from the twin albums Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty through From the Mars Hotel. Then came Blues for Allah, an obvious departure from these classic Dead albums but one that’s not easy to put a label on.

Blues for Allah is the first entry in the “modern” Grateful Dead catalog. By this point we had all but lost the spacy guitars and warbling keys that were synonymous with the ‘60s and ‘70s sound. In their place we got funky bass lines, a spatter of horns, and experimentation, so much experimentation.

The album isn’t as concise as some other Dead records; it jumps all over the place. You have a couple psychedelic tracks like “Franklin’s Tower,” but you also have the oddities like “Crazy Fingers,” a reggae song that sounds more like Stick Figure than the Grateful Dead. Blues for Allah also features two bridge jams, instrumental songs that bridge the gap between two stylistically different tracks, helping them flow into one another. These two songs, “King Solomon’s Marbles” and “Sage & Spirit,” are important for the continuity of the album; however, in the modern day, when listening to an album straight through isn’t so common, I would have to imagine these two usually get skipped. The album ends with its title track, “Blues for Allah,” a twelve-minute jam that never quite takes flight in the way I would like, mounting to a peak that looks more like a plateau once you get there.

All that being said, it may sound like I didn’t enjoy Blues for Allah, but it’s actually one of my favorite Dead albums. It isn’t a bad record; it’s just different, and that’s what the Grateful Dead were all about: being different. The band put emphasis on always changing and growing; to them, their music was a living organism that had to constantly evolve to survive. Blues for Allah was the next evolution for the Dead; it kicked off an era that gave us countless hits and produced my favorite of their albums, Shakedown Street.

Blues for Allah is strange even by the Grateful Dead’s standards, but it works. The album carries the spirit of what the Dead were all about, and it gave us a couple of timeless songs. It may not be their most popular work, but there is a reason why this record is still being played today. It’s a masterfully crafted album that will never get stale no matter how many times you listen to it. For that reason, I guarantee you that in another fifty years you’ll still hear it spinning in record stores.